Photo: PINS Daddy

It has officially been 1 week since I’ve been back in the U.S., so it’s only right that I get back to writing my confusions, my exploits and my experiences. Thanks for loving me through the hiatus. It’s only right that – 8 days fresh off the wings of a United flight – I come back to writing with a few questions for you’se guys who call this place home. Help me understand how this place works. There are so many things I just don’t get anymore.

1 – Why do I have to fill out the Customs forms if I have global entry? I feel like DHS & CBP just have a lot of paper lying around and they want to get rid of it by dumping it on those of us who don’t need it, but don’t yet know we don’t need it. Keep yo’ paper, bruh! I have enough luggage to worry about.

1a. Why doesn’t every American with a passport have global entry tho’?

1b. Who has life minutes to waste in long lines in airports tho’?

2 – Why is everything in the super market in a box or a plastic bag? Forgive my amnesia on this subject, but I’m going to repeat Chimamanda Adichie, who only recently joined our sacred Barnard sistahood (we’ll keep her tho’) and is also eloquent with a writer’s pen, “EAT REAL FOOD.” I was so sad walking through Trader Joe’s this week and Whole Foods last week when I felt like I walked out with more packaging than actual food. 5adayCSA here I come!

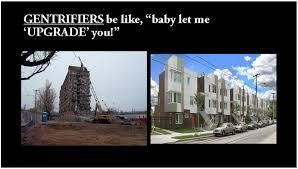

3 – Why is gentrification happening in every neighborhood in the country at this very moment in time? I mean, literally, I could trace the eastern seaboard with a litany of Brown people tears over gentrification. I’ve been in 3 states in the last 8 days and in each town I visited I’ve heard lamentations of the erasure of people of color, the displacement of low and middle-income families, and reverse White flight. I just can’t figure out why now? I could get into the race issues here, but I’ll just settle on simply asking “why are all the White folks moving?”

4 – What are cops for anymore? People (of color, predominantly) are more afraid than ever to cross paths with police officers, so I’m kinda wondering how exactly can they be useful. In theory, yea, public safety, blah, blah I get it (ish), but really I can’t be the only one wondering… 4a. when is it safe to call them exactly? 4b. Could I live with myself if something bad happened either way? or 4c. Would I be alive after they left?

Pinterest – saved by Rebecca Mendez

5- Last, but not least, how many housewife shows are actually on the air right now? There are Real Housewives of like 12 towns & 49 states; 1st and 2nd wives clubs in satellite cities; Celebrity, Jail and Sister wives. I mean, we get it, shows about nuclear, dysfunctional families will keep women with disposable income glued to the TV looking at commercials and buying stuff we don’t need to mimic people we don’t like. But, c’mon, let’s do better. I’d trade you 20 of these wife shows full of fiancees & divorcees for just 10 HGTV channels, preferably in metropolitan cities where one can purchase a 3 bedroom house for less than $400,000 USD. A real wife can dream…

Riddle me that.